The Philosophy of the Bhagavadgita :

Chapter 1: The Universal Scope of the Bhagavadgita :

Part-a.

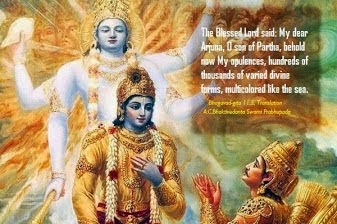

The Bhagavadgita is a well-known gospel. Very few might have not heard the name, ‘Bhagavadgita’, for it is almost universally accepted as a scripture, not merely in a sense of holiness or sanctity from the point of view of a religious outlook, but as what has been regarded as a guide in our day-to-day life, which need not necessarily mean a so-called religious attitude of any particular denomination. Our life is vaster in its expanse than what we usually regard as a vocation of religion. And if religion remains just an aspect of our life and does not constitute the whole of life, the Bhagavadgita is not a religious scripture, because its intention is not to cater to a side of our nature or a part of our expectation in life, but the whole of what we need, and what we are. This special feature of the Bhagavadgita makes it a little difficult for people to comprehend its significance and message. While hundreds of expositions there are on this great gospel and several commentaries have been written and are being written on it even now, it is difficult to believe that its meaning has been completely grasped, as it becomes a novelty after novelty as we go deeper and deeper into it. The more we read it, the fresher does it appear before our eyes, like the rise of the sun every morning. This speciality and comprehensiveness which is the approach of the Gita is what makes it a little distinct from the other well-known religious guidelines. We have heard it often said that it is an episode in a large epic of India, known as the Mahabharata, and we regard it as a teaching given by someone to someone else in some ancient times in a particular context of those early days. We are likely to read this epic as a story, like a drama or a play, for our diversion and emotional satisfaction. But this epic of which the Bhagavadgita is an episode is not a story come from a grandmother to a child, though it is narrated in the fashion of a dramatic performance with images and artistic touches of characters which portray the various facets of human liking and attitude. What inspires us and stirs us when we read an epic of this kind is the sympathy that exists between these characters and the various phases of our own personal lives. We find ourselves somehow in these epic characters. We are drawn to these images of persons and situations on account of there being a representation, as it were, of what we ourselves are at different moments of time or in the layers of our own personalities. All these people, the heroes and heroines, the dramatize personae of the Mahabharata, are present inside us, and we ourselves are these at different occasions and times. We have layers of personality in us and these various layers correspond to the ideal images that are portrayed in the characters of this great epic, the Mahabharata. Why are we inspired when we read the plays of Shakespeare? Because we are present there. Every one of these special characters that Shakespeare, for instance, delineates with the masterly stroke of his pen corresponds to our own self in some manner or the other. Every character of Shakespeare is present in us and we are every one of these. So, we are in sympathy within, we are in rapport with all these characters, and so we are stimulated by a study of his plays. It is human nature as such that is displayed in the dramas of Shakespeare, the epics of Homer or the Mahabharata. It is not the story of some people that lived sometime ago but a characterization of all people that may live at any time in the history of the world. They are not stories of certain people only; they are stories of people as such, of any person, and the nomenclature of these personalities is only by the way, the essentiality is the attitude, the character and the conduct and the personal and social features that they demonstrate in their temporal existence. The characters are perpetual features in the evolution of the cosmos, while the vehicles which embody or enshrine these characters may vary. These are the specific stages through which the world has to pass, and every individual is a part of the world. Everyone has to traverse every one of these stages. Every character is every person and vice-versa. Thus, while the epic of the Mahabharata, like some other epics also of this nature, attempts to portray the culture of an entire nation, or, we may say, the culture of humanity in general, it pinpoints its teachings at a central occasion which it regards as the most convenient hour to give its message in its essentiality. The Bhagavadgita is the kernel of this vast expanded fruit of the Mahabharata, which has matured out of the tree of the culture of India. The philosophic messages which are given in the various chapters of the Gita are dramatically portrayed in the characters of the story of the epic. The one explains the other. The narrative of the Mahabharata, the epic aspect of this great work, is a performance, in the stage of humanity, of the message that is to be conveyed in the form of the Bhagavadgita; and, when we look at it the other way round, the Bhagavadgita is what is intended behind the whole narration of the Mahabharata. The great author of this epic achieves a double stroke by his masterpiece that he has given to mankind. He gives directly a message that has to go into our souls, and at the same time makes it appealing to the various psychological features which constitute our emotional personality. And, as I mentioned a little earlier, its message is not religious in the common sense meaning of the term; it does not teach any ‘religion’, if by religion we mean the so-called faiths of the world that are prevalent today, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, or any sectional cult though under an outer cloak, we may imagine that it is a Hindu scripture. It is a scripture that has originated in India, may be by an accident or a contextual necessity in the history of the universe. But it is not meant only for the people of India, it is for people, and for all people, and all people for all times. It is, therefore, not a message that Krishna gave to Arjuna so that we can just set it aside as something relevant to those times and not applicable to these days. It is a message of eternity, and it has a timeless significance for every one of us. It does not get rusted or worn out by the movements of time or the changes that take place geographically, socially or politically. The vicissitudes of life have no impact upon this message, because it arises from a source which transcends the transitions of life. And in a few words which occur towards the end of each chapter, as a colophon thereof, we are given an indication of the eternity, practicality and divinity of its content. It is supposed to be a message which embodies the knowledge of what is ultimately real, and not merely temporarily valuable or significant. When everything passes away, something shall remain, and what that something is, is the object of the quest of this knowledge which is embodied in the Bhagavadgita. It is called ‘Brahmavidya’, the knowledge of the Absolute, Brahman. The reality that cannot further be transcended is called the Absolute. It is so called because it is not related to anything else; it is non-relative Being. I am socially related to you, and you are related to me; and therefore our empirical existence is relative, one thing hangs on the other. But the Absolute does not hang on something else for its description; characterization or existence. In our case, or in the case of anything, existence is conditioned by other existences. For instance, we are dependent on various factors for our life in this world – we require sunlight, water, air, food, we require social co-operation and protection and many other things of this nature, so that if these external conditioning features are absent, our personal or individual existence may be wiped out in a few days. We have no independent status of our own, we depend on other factors for our existence. There is a mutual dependence of characters, individuals and things in this world. Therefore, we say, the world is relative, and it has no absolute reality. But this relativity of things in the world is a pointer to the possibility of the existence of something which is not relative. The idea of relativity cannot arise unless there is something which makes us feel that things are relative. That which enables us to be conscious of the relativity of things cannot itself be relative. So, there is a necessity to admit the existence of that which is not relative, and it is designated, in scriptures like the Upanishads, as Brahman. This is a name that we give, for the purpose of our own descriptive understanding, to that which must exist as transcendent to anything that we see with our eyes or anything that we can conceive with our minds. The Bhagavadgita is the knowledge of the Absolute, Brahmavidya, which is mentioned at the end of each chapter. It is also called an Upanishad – something very strange to normal sense. It is an esoteric teaching, plumbing the depths of the essentiality of things behind the veneer of encrustations in the shape of names and forms. An Upanishad is a secret teaching. It is secret because it has concern with that which cannot be seen with the eyes. It is not related to appearances. The names and forms of the world are not the subject of the Upanishad. Its relationship is with that which is behind the names and forms. As its connection is with that which the senses cannot perceive, even the mind cannot think adequately, it is to an extent regarded as a secret and therefore it is an esoteric teaching; it is ‘Upanishad’. The Upanishads being such, the Bhagavadgita which is regarded as the quintessence of the teachings of the Upanishads, is also venerated as an Upanishad. And, interestingly before us, it is mentioned in the plural, ‘Iti Srimad-Bhagavadgitasu Upanishatsu.’ It is not one Upanishad. It appears to be many Upanishads brought together in a forceful concentration. Perhaps, each chapter is an Upanishad by itself; each chapter is a message by its own status. Well, there have been people who thought that even a single verse can be regarded as a message. Devotees of the Bhagavadgita have received inspiration from even one verse. One may open any page of the Bhagavadgita, and one will find there something which will inspire the heart at once and lift one up from the turmoils of the ordinary life that one lives in the world. So, it is a plurality of the Upanishads, and not one Upanishad merely. All the Upanishads are here, condensed in their supra-essential essence. So, it is said, ‘Bhagavadgitasu’, again, in the ‘songs’, not merely the song of the Lord. Many messages are conveyed through the various chapters and the verses so that every disease conceivable of human nature can be remedied by some medicine or the other that is there in the form of some word of the Bhagavadgita. It is a remedy for every illness of life. It is also considered as an essence of all the scriptures – sarva-shastramayi gita. It is said many a time that all the Shastras, all the lessons that we can have anywhere can be found here in some form. It is an esoteric, secret teaching concerning the reality behind things and it does not cater merely to a sentiment that is attached to appearances. It is intended to do us good in the ultimate sense of the term and not merely to satisfy our imagination by temporarily stimulating an emotion. It is not also an academic or theoretical message or gospel concerning the nature of the Absolute, for, it is, at the same time – and this is a special character, again – a practical guideline for the purpose of treading the path to the realisation of his ultimate reality. It is, therefore, a ‘Yoga-Shastra’, not only a Brahmavidya. We will find very few texts which combine these two aspects of teaching. It is not an emphasis that is laid on only one side of our life, but all the sides are equally balanced. It is a theory and a practice; and practice is preceded by theory. The comprehension of the technique to be employed in any particular line of action is called theory.

Swami Krishnananda

To be continued ...

Comments