The Relevance of the Bhagavadgita to Humanity 8-5: Swami Krishnananda.

Monday 14, October 2024, 06:15.

The Relevance of the Bhagavadgita to Humanity:

Chapter 8: The Realism and Idealism of the Bhagavadgita-5.

The First Six Chapters of the Bhagavadgita:

Swami Krishnananda

(Spoken on Bhagavadgita Jayanti

========================================================================================

Our personality is made up of certain levels. The personality of ours looks like an abstract thing. It is not necessarily the physical body. It is abstract in the sense that a human being is also some abstract principle, finally. We cannot say that we are a body, though it looks like we are that only. All the values that we admire in life are not necessarily material and physical, because we have seen that a materially well-placed and physically well-built personality is not necessarily a complete personality, not a satisfied personality. Our involvements are the levels of our personality. Each one has to understand for oneself what are the involvements of oneself. There are immediate involvements, and other subtle ones which come as layers inside, which can be considered a little later. But immediate problems are immediate involvements. A pressing situation which has to be attended to just now is the most immediate involvement of a person, though there are other involvements which are also important enough, and it takes a little time for us to go deep into this issue of what our involvements are. We have to take time to understand that. Sometimes it may look that we are involved in nothing. Some people feel, “What involvement have I got? I am a free man.” It is not so simple as that. Involvement means the recognition of anything outside you as real to the extent it affects your existence. Is there anything real outside you, or is there nothing real outside you? No sensible person will say there is nothing outside them. We feel that there are certain things outside us, and they are real to us, and to the extent that we accord reality to that which is outside us, to that extent we are involved in it. The concession of reality that we have granted to something outside us is also the extent to which we are involved in it, and no one can say that it is not involvement.

Various types of involvements will be unravelled gradually as we move through the chapters of the Bhagavadgita. The lowest involvement, at least as we have it described in the Mahabharata and the Bhagavadgita, is the politically motivated involvement. Every person as a citizen of a nation or a country, every person who is internationally conditioned in some way or the other, is a political unit. And it is difficult for anyone to say that such a condition is absent entirely. Clarified, dispassionate thinking is necessary to accept the extent of this involvement. The security that we require politically and the obligations that we owe politically in any manner determine the extent of our involvement politically. Political involvement does not necessarily mean being an officer in the government or a soldier on the battlefield. Our very existence as a human being, conditioned by an atmosphere of outward administration, is a political involvement. A reply from that point of view also has to be given. It is our obligation to pay a tax. Now, we may think this is not a spiritual instruction. What connection do spirituality and religion have to paying a tax to the government?

We have to understand religion properly, as I mentioned a little before. Religion is not avoiding duty. In fact, the whole of the Bhagavadgita is a gospel of duty. If to be religious is a duty, then religion as a duty, perhaps as a comprehensive duty, will also have the sense to accept various other aspects of duty which have to be included within this comprehensiveness of duty, which is religion. Religion is sometimes said to be the final duty of man, the only duty of man, and so on. But, as I mentioned at the very outset, that would be to take an idealistic view of things, holding on to an ideal which is ahead, and forgetting the fact that which is ahead, in the future, is not unconnected with the present. Realism is the characteristic of the present. Idealism is the characteristic of the future. Now, how can you have only a future without the present?

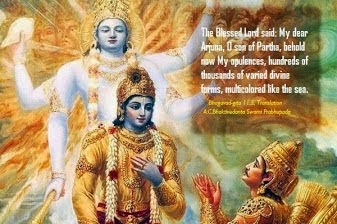

So the initial answer of Sri Krishna was on the basis of a duty that Arjuna owed from the level of his being a soldier. It was told that Arjuna was a Kshatriya. This raises several questions. Why was he called a Kshatriya? How do we find out who is a Kshatriya? And what is his duty? If we have some way of deciding what are the characteristics of a person, in the light of which we call a person a Kshatriya, and so on, and in that light we are able to decide the duty of a person, we have also to answer another question: Why should that particular person do only that duty, and not some other duty? Why should not a soldier be a priest in a temple? What is the harm? Because it is believed that to be a worshiper in a temple is perhaps a holier occupation than that of a soldier in the battlefield, why should I not be a holy man? Why should I do unholy things as a soldier in the battlefield? These questions may arise in a religious mind: It is better to be a holy man than to be a fighter in the battlefield. Arjuna mentions this. “I shall be a beggar. I shall go to the forest and live the life of a mendicant. Śreyo bhoktuṁ bhaikṣyam apī 'ha loke (BG 2.5): “Is it not good to live on alms and not do this, which you call a duty now?” This will raise some interesting questions which people take notice of and, in answering which, a muddle is made by most people. What is the duty of a person, and how do we find out which person has to perform what duty? Briefly the Bhagavadgita refers to this. It does not give a long commentary, but this brief statement is enough suggestion for a commentary on it.

Many questions arise in this context. Who is to do what duty, and why should anyone do any duty at all? And finally, how will you reconcile yourself to a conflict that is likely to arise in your mind between a future ideal, which you consider as superior, and the present pressing problem, which you consider as inferior? We always have an eye on the superior, better values of life than the inferior ones. If we can get the higher one, why go to the lower? But a reconciliation has to be struck between these two, because the lower one is not an unreal value. We have already considered this issue, that lower realities are not unreal. As long as they are real, they are very, very important and significant. We put our foot into the future only by lifting it from the present. It implies that we are already in the present, and therefore it is a reality. We are not in a vacuum just now. It is not some vacuum reality through which we move. We will move from a lesser reality to a higher reality. These issues are clenched in a few verses in the Second Chapter of the Bhagavadgita, at the very commencement, which you will find very interesting.

End

Next

Chapter 9: The Classification of Society

Continued

.jpg)

Comments