The Spiritual Import of the Mahabharata and the Bhagavadgita : Ch-3. Part-3.

3: The World is the Face of God : 3

But suffering is also a kind of catharsis that is administered to the soul to purge its sins. It is not a curse that has descended upon us. Suffering is not a curse. It is a cleansing process, like a fever that comes to clean the system and throw out the toxic matter from the body. We suffer due to certain automatic reactions that are set up by certain actions. Actions are performed by people without the knowledge of the nature of the consequences that these actions would produce, because the consequences are conditioned by factors beyond one’s thought. We have some idea as to what we are capable of doing, but we cannot have a complete idea of what we fall on, because the effects are determined by various factors other than merely the idea about it in the mind of the doer of the action.

So, unforeseen consequences retaliate upon the individual; they are called sorrows. They are called sorrows because they are not in conformity with the likes or the desires of the individual at that given moment of time. If we are thrown into the Ganga and feel chilled inside, that would be a sorrow indeed; but if a fish is thrown into the Ganga, that would not be a sorrow for it. So it is the condition of the individual that determines a particular experience to be either pleasant or otherwise. Ultimately there is no such a thing as absolute pleasure or absolute pain—they do not exist. They are always relative to the nature of the individual experiencing them. However, such consequences, when they rebound upon the individual, become sources of pain on account of one’s not being prepared for them. Such are the sorrows of the spiritual seeker also, because of his immature efforts in the direction of God-realisation, not knowing his true relationship to God, because there is a powerful world between us and God. This should not be forgotten. There is something between the seeker and that which we seek, and if we completely ignore the presence of that which is between, it would be a mistake. The God which we seek cannot be directly seen except through the spectacles of the world.

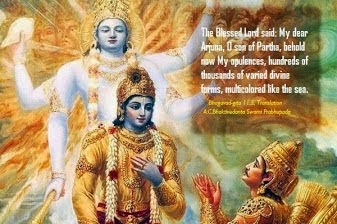

In the Ramayana, Tulsidas gives a beautiful description of Rama, Sita and Lakshmana walking, with Sita in the middle, and gives the image by saying that Sita was there as maya between brahma and jiva. Likewise, there is this world before us, which we are likely to unintelligently ignore in our enthusiastic aspiration for God. The world is the face of God; it is the fingers of the hands of God Himself moving, and the so-called appearance of the world is rooted in the reality of the Absolute. There is a very unfortunate aftermath of this interesting analysis, namely, we ourselves are a part of this appearance, and to put on the unwarranted status of the reality in ourselves, while we are looked at as appearance, would be to disregard the law that operates in the realm in which we are placed. Appearance is, after all, an appearance of reality—it is not an appearance of nothing. If it had been nothing, the appearance itself would not be there. Inasmuch as the appearance is of reality, it borrows the sense of reality. The snake is in the rope, yes, but we must know that the rope is not absent. Though the way in which the rope is seen may be an erroneous perception, the fact of the rope being there cannot be ignored—that is the reason why the snake is seen at all. If the rope is not there, even the snake would not be there. It is the reality of the Absolute, the presence of God that is responsible for the appearance of the world.

To be continued ...

.jpg)

Comments