The Spiritual Import of the Mahabharata and the Bhagavadgita : Ch-2. Part-5.

2: Challenges of the Spiritual Seeker-5.

Many a time we feel as if we have been lost and have been forsaken totally. Even advanced seekers, saints and sages have passed through this critical moment of the sinking of the soul when, in anguish, words which would not ordinarily come out of their mouths do come and did come in respect of God. ‘God, are You blind?’ can be a poem of a great saint when no action is taken to redress the sufferings of the seeker, no blessing is bestowed upon him, no vision comes forth and he is only put to the grind and made to suffer more and more, more critically than the world would have tortured him had he been in the world. All these are peculiar psychical conditions in which we have to find ourselves and for which we have to be prepared, and no one is exempt from the law of the mind. Whether it is Buddha’s mind or it is the mind of a rustic in the fields, the structure of mind is the same, and in its evolution it has to pass through all the stages of agonising suffering, emotional tearing, as it were, on account of the tussle that one has to undergo between the spirit within and the spirit without.

This spirit that is implanted in us suffers for union with the spirit outside, the Absolute. There is its critical moment. It is as if we were going to embrace the ocean. This experience has been compared in many ways to merging into fire, tying a wild elephant with silken threads, swallowing fire, etc. The problem arises on account of the peculiar nature of the mind. The mind is addicted to sense experience. It is accustomed to the enjoyment of objects, and it is now attempting to rise above all contacts and reach the state of that yoga which great masters have called asparsha yoga—the yoga of non-contact. It is not a union of something with something else; that would be another contact. It is a contact of no contact. It is difficult to encounter because of a sorrow of the spirit, deeper than the sorrow of the feelings, which even a saintly genius has to experience. The deeper we go, the greater is our sorrow, because the subtle layers of our personality are more sensitive to experience than our outer, grosser vestures. We know very well that the suffering of the mind is more agonising than the suffering of the body. We may bear a little sorrow of the body, but we cannot bear sorrow of the mind—that is more intolerable.

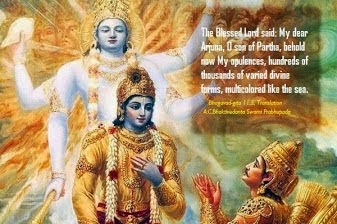

There is such a thing called the sorrow of the spirit, though it may look like an anomaly. How could there be sorrow for the spirit? Yes, there is some kind of situation in which our deeper self finds itself in its search for the Absolute. These are all interesting stages that are in mystical theology and the yoga of the advent of the spirit. Some of the songs and poems of the Vaishnava saints of the south, the Alvars, particularly the Nawars, and some of the rapturous expressions of the leading Shaivite saints, will be enough examples to us of the inexpressible and intricate spiritual processes through which the seeker has to pass. We are accustomed merely to a little japa, a little study of the Gita that we chant and repeat by rote every day like a machine, and we feel that our work is over, that we have done our sadhana. The deeper spirit has to be touched, and it has to be dug out like an imbedded illness. When it is pulled out there is a reaction, and the reaction is a spiritual experience by itself, through which Arjuna had to pass. A little of it is given to us in the first chapter and the earlier portions of the second chapter of the Bhagavadgita.

To be continued ...

Comments